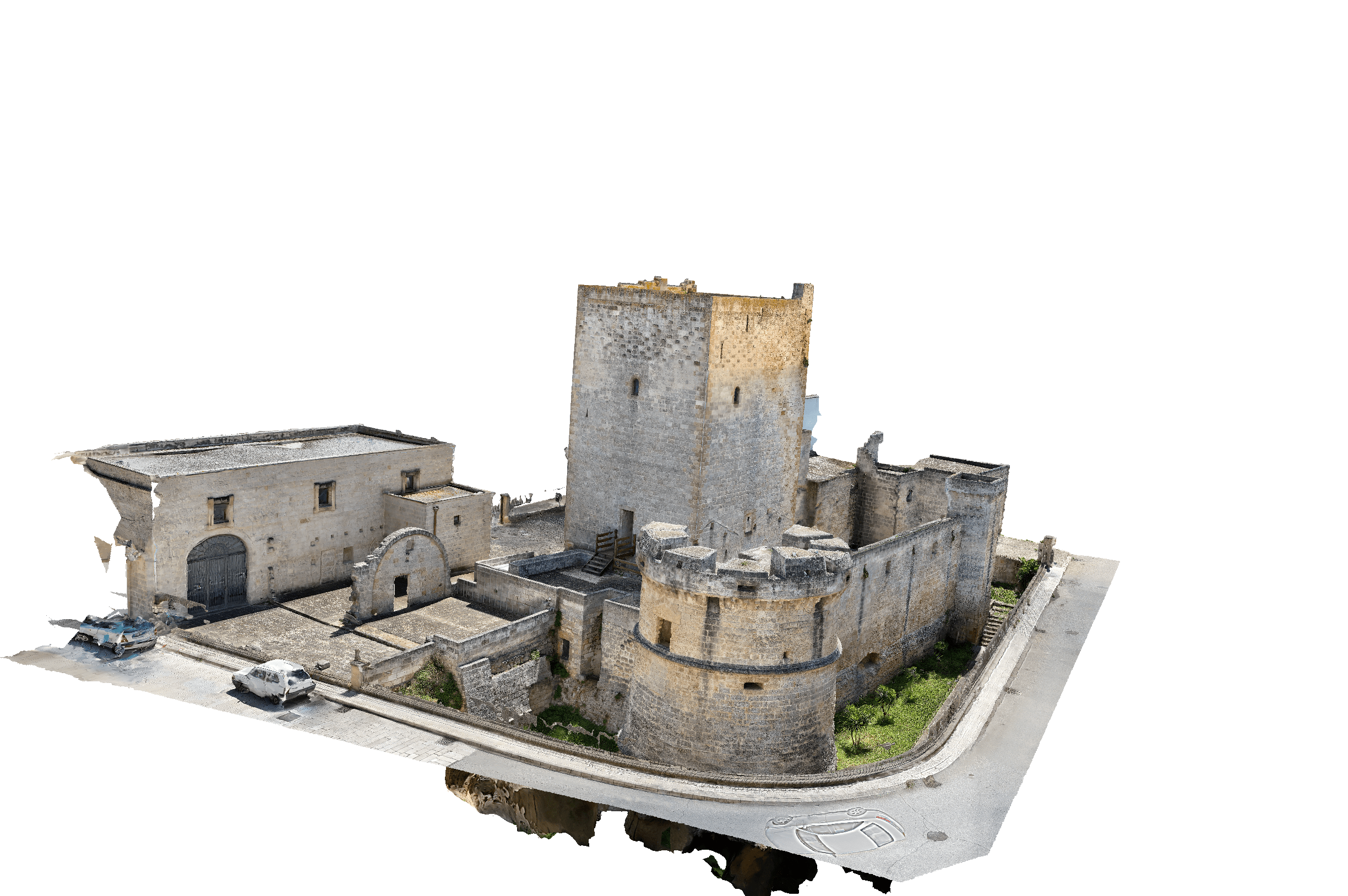

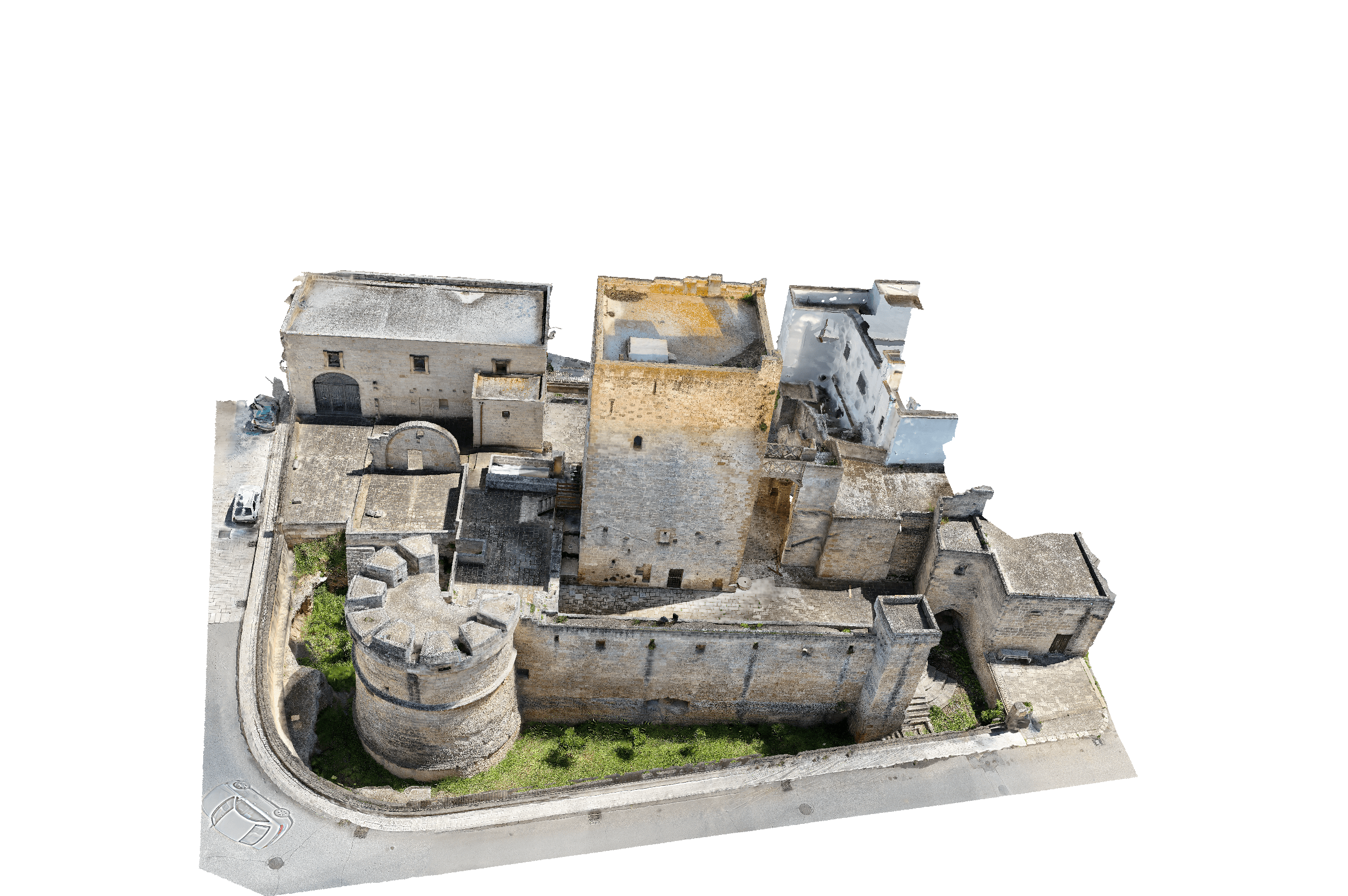

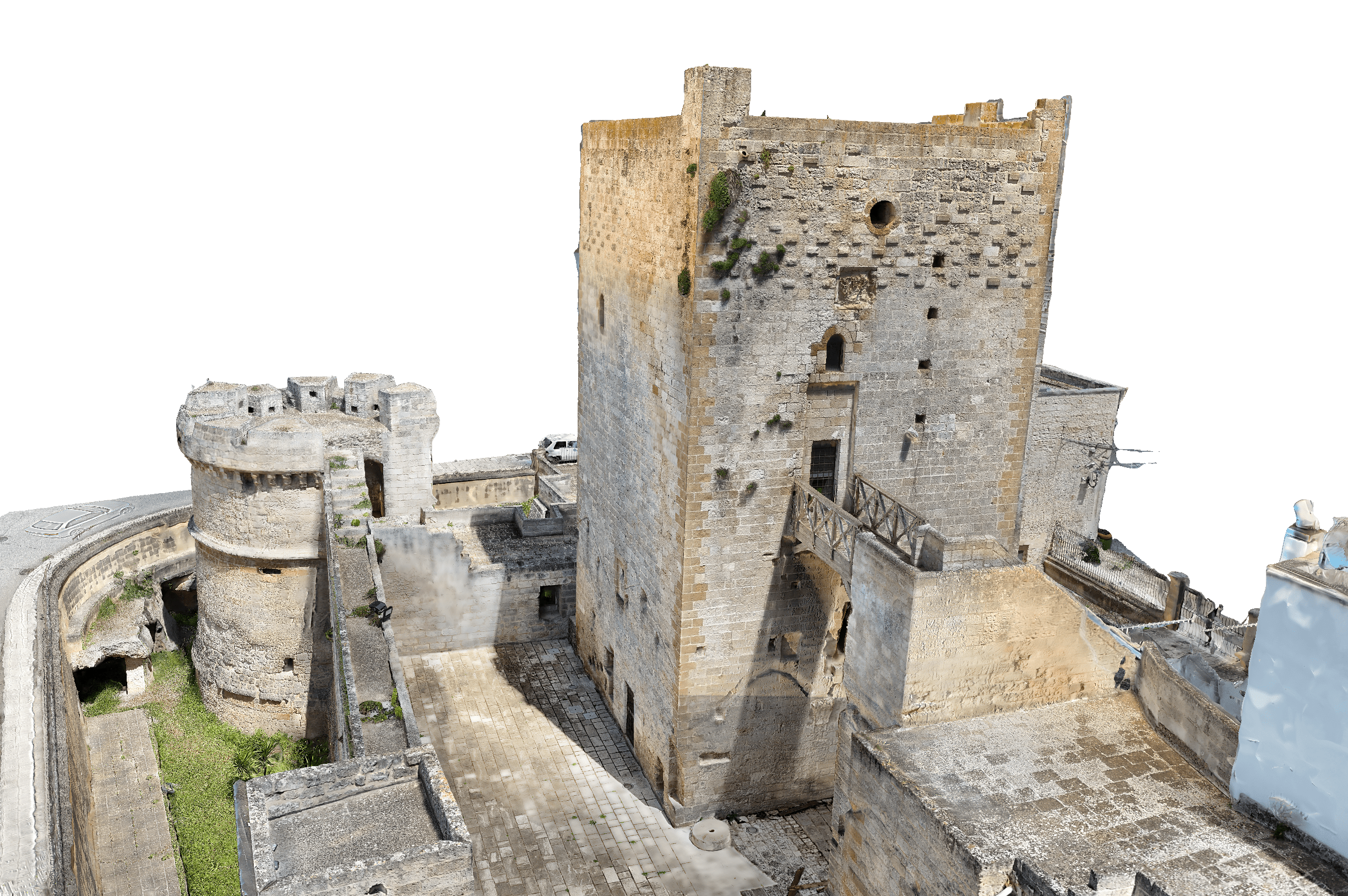

Ogni paese ha i suoi silenzi. Ad Avetrana, due pietre li raccontano. Una è antica, sobria, incisa con mani commosse. L’altra, più recente, guarda in alto, verso la luce. Sono i due monumenti dedicati ai caduti di guerra. Due forme diverse. Due epoche lontane. Un solo messaggio: non dimenticare. Il primo nasce dopo la Grande Guerra. Tra il 1915 e il 1918, anche Avetrana mandò i suoi figli al fronte. Erano contadini, artigiani, studenti. Molti non tornarono. Altri tornarono cambiati per sempre. Nel 1924, l’Associazione Combattenti e Reduci volle ricordarli. Fu celebrata una messa solenne in piazza, il 4 novembre. Ma quel dolore meritava di diventare pietra. Servivano nomi, servivano fondi. Ci volle del tempo. Nel 1932, grazie all’impegno del commissario prefettizio Alessandro Selvaggi, fu realizzata una lapide marmorea, scolpita da Raffaele Giurgola di Lecce. Fu affissa sulla torre dell’orologio, nella piazza del Popolo. Era semplice, solenne. Un segno concreto. Una memoria che restava visibile ogni giorno. Poi, vent’anni dopo, la storia si ripeté. Il 10 giugno 1940, l’Italia entrò nella Seconda Guerra Mondiale. Avetrana lo seppe dalla radio. Nessun entusiasmo. Solo silenzio, lacrime e paura. I giovani partirono. Chi per il fronte greco, chi per l’Albania, chi per il gelo russo. Le case si svuotarono. Le madri pregavano. Le lettere smettevano di arrivare. Un giorno un aereo sorvolò il paese, lanciando volantini: “Abbandonate le abitazioni. Il bombardamento è imminente.” La gente scappò nelle campagne, dormendo nei pagliai. E poi arrivò la notte di Taranto, l’11 novembre 1940. Gli aerei inglesi bombardarono la flotta italiana. Il cielo si illuminò. Ad Avetrana si sentivano i boati. E anche se le bombe non caddero qui, la guerra era vicina. Fin troppo. Nel ’41 arrivarono le truppe italiane. Furono ospitate nel vecchio teatrino, nel palazzo Parlatano, in case private. Nel 1942 e 1943, altri reparti si stabilirono tra Torre Colimena e Punta Presutti. Lì sorsero torrette d’avvistamento. Una di esse conserva ancora un’incisione: “Grasso T.V. – 21.5.43”. L’8 settembre 1943 venne annunciato l’armistizio. Si sperò nella pace. Ma la guerra non era finita. Una notte, un mitragliamento aereo colpì alcune abitazioni in paese, compresa quella dell’arciprete. Fu usato un sistema d’allarme d’emergenza: il martello sulla campana della chiesa madre. La vita era dura. Il cibo era razionato, le famiglie sopravvivevano con le carte annonarie. Il Comitato ONMI aiutava le madri e i bambini. Le donne protestavano per avere più farina. Si viaggiava a cavallo e gli autobus erano ridotti a una corsa al giorno. Poi, con la caduta del fascismo, qualcosa si spezzò. Le scritte inneggianti al Duce vennero cancellate. I fasci distrutti dalla scuola, dalla torre dell’orologio. Avetrana cercava di ricominciare. Ma un’altra esigenza emergeva: la memoria andava rinnovata. Il paese aveva bisogno di un segno nuovo, capace di parlare anche ai giovani. Così, nel 1992, grazie all’impegno dell’Associazione Nazionale Combattenti e Reduci di Avetrana, si decise di erigere un nuovo monumento. L’area scelta fu piazza Bengàsi, un crocevia urbano ormai trascurato, ma carico di storia. Lì un tempo c’era uno dei pochi pozzi che dissetavano la popolazione. E da quel simbolo di vita si partì. L’architetto Giuseppe Nigro progettò un’opera diversa da tutte: una piramide. Alla base, un grande cilindro in pietra calcarea, che richiama proprio quel pozzo, simbolo della vita condivisa, dell’acqua che unisce. Sopra, si innalza una piramide triangolare, forma potente e universale. Perché una piramide? Perché fin dall’antico Egitto, le piramidi rappresentano l’eternità, la continuità oltre la morte. Sono monumenti incrollabili, costruiti per resistere al tempo, per collegare la terra al cielo. Quella di Avetrana non è una semplice forma: è un’idea di passaggio. Il basamento ospita due aiuole con alberi, simbolo dell’attaccamento alla terra. La piramide sale verso la luce. Alla sommità, una cuspide vitrea trasparente lascia filtrare il sole e la notte, al suo interno, un faro parabolico si accende, proiettando verso l’alto un raggio simbolico. Un’anima che si libera, una memoria che non si spegne. Sul lato rivolto a oriente, ogni mattino il sole sorge e illumina i nomi dei caduti, incisi nella pietra. È come se ogni giorno, quei nomi risorgessero. E la notte, quattro fari rendono il monumento visibile anche nel buio, come una presenza silenziosa che veglia sulla città. La pietra utilizzata è doppia: pietra di Trani e Soleto, due tonalità alternate che creano un contrasto visivo forte. Un dialogo tra la vita e la morte, tra il conosciuto e l’ignoto. Tra ciò che è stato e ciò che resta. È un monumento che non impone, ma racconta. Non si limita a ricordare: ci chiede di comprendere. E così, oggi, Avetrana ha due voci. Due luoghi di memoria. Uno antico, nato dal dolore. Uno moderno, nato dal bisogno di dire: “Ci siamo ancora e ricordiamo.” Due forme, due epoche, ma una sola verità: la memoria è il fondamento della pace. E ogni nome inciso è una storia, una casa, un abbraccio che il tempo non può cancellare. Quando passi da piazza Bengàsi, fermati un momento. Guarda quella piramide. Non è solo una scultura. è un ponte. Tra chi c’è stato e chi c’è ancora. Tra la guerra e la speranza. Tra l’oblio e il ricordo

Every Town Has Its Silences In Avetrana, two stones tell them. One is ancient, sober, carved by moved hands. The other, more recent, looks upward, toward the light. They are the two monuments dedicated to war casualties. Two different forms. Two distant eras. One single message: never forget. The first was born after the Great War. Between 1915 and 1918, Avetrana too sent its sons to the front. They were farmers, craftsmen, students. Many never returned. Others came back forever changed. In 1924, the Association of Combatants and Veterans wanted to remember them. A solemn mass was held in the square on November 4th. But that pain deserved to become stone. Names were needed, as were funds. It took time. In 1932, thanks to the efforts of Commissioner Alessandro Selvaggi, a marble plaque was created, sculpted by Raffaele Giurgola from Lecce. It was affixed to the clock tower in Piazza del Popolo. It was simple, solemn. A concrete sign. A memory visible every day. Then, twenty years later, history repeated itself. On June 10, 1940, Italy entered World War II. Avetrana heard the news on the radio. No cheers. Only silence, tears, and fear. Young men left: some for the Greek front, some for Albania, some for the Russian frost. Homes emptied. Mothers prayed. Letters stopped arriving. One day, a plane flew over the town, dropping leaflets: “Abandon your homes. Bombing is imminent.” People fled to the countryside, sleeping in haylofts. Then came the night of Taranto—November 11, 1940. British planes bombed the Italian fleet. The sky lit up. In Avetrana, explosions could be heard. And even though the bombs didn’t fall here, the war was close. Far too close. In 1941, Italian troops arrived. They were housed in the old theatre, in the Parlatano palace, and in private homes. In 1942 and 1943, more units settled between Torre Colimena and Punta Presutti. Observation towers were built. One still bears an inscription: “Grasso T.V. – 21.5.43”. On September 8, 1943, the armistice was announced. There was hope for peace. But the war wasn’t over. One night, an aerial strafing hit several homes in town, including the archpriest’s. An emergency alarm system was used: a hammer striking the bell of the mother church. Life was hard. Food was rationed, families survived with ration cards. The ONMI Committee helped mothers and children. Women protested for more flour. People traveled by horse, and buses ran only once a day. Then, with the fall of Fascism, something broke. Slogans praising Mussolini were erased. Fascist emblems were removed from the school and the clock tower. Avetrana tried to start again. But another need emerged: the memory had to be renewed. The town needed a new sign, one that could speak to the younger generation too. So, in 1992, thanks to the efforts of the National Association of Combatants and Veterans of Avetrana, a new monument was commissioned. The chosen area was Piazza Bengàsi, a neglected urban crossroads, but rich in history. Once, one of the town’s few wells stood there, which had quenched the population’s thirst. And it was from that symbol of life that they began. Architect Giuseppe Nigro designed something unlike anything before: a pyramid. At the base, a large cylindrical block of limestone recalls that very well— a symbol of shared life, of water that unites. Above it rises a triangular pyramid, a powerful and universal form. Why a pyramid? Because since ancient Egypt, pyramids represent eternity, continuity beyond death. They are unshakable monuments, built to withstand time, to link earth to sky. Avetrana’s is not just a shape: it is an idea of transition. The base hosts two flowerbeds with trees, symbolizing attachment to the land. The pyramid rises toward the light. At the top, a transparent glass cusp lets sun and night filter through. Inside, a parabolic spotlight shines upward, projecting a symbolic beam. A soul being freed, a memory that does not fade. On the eastern-facing side, every morning the sun rises and illuminates the names of the fallen, carved in stone. It is as if, each day, those names are reborn. And at night, four spotlights make the monument visible in the dark, like a silent presence watching over the town. Two types of stone were used: Trani and Soleto, two alternating tones that create a strong visual contrast— a dialogue between life and death, between the known and the unknown. Between what was and what remains. It is a monument that does not impose but tells a story. It doesn’t just commemorate—it invites understanding. And so, today, Avetrana has two voices. Two places of memory. One ancient, born of grief. One modern, born of the need to say: “We are still here, and we remember.” Two forms, two eras, but one truth: memory is the foundation of peace. And each engraved name is a story, a home, an embrace that time cannot erase. When you pass through Piazza Bengàsi, stop for a moment. Look at that pyramid. It is not just a sculpture. It is a bridge— between those who were and those who remain, between war and hope, between oblivion and remembrance.